The high-level impact and ongoing effects of El Niño

The humanitarian impact and the economic ripple effects of El Niño are both numerous and interlinked. In an increasingly globalised and integrated world, disentangling and insulating individual effects on a country, population segment, or sector-basis is, therefore, difficult. However, a number of higher-level conclusions and forecasts can be made regarding agriculture, food security and food prices, the (disproportionate) impact on the poor, and the second-order effects on inflation, government spending and government policy, the labour market and investment opportunities.

Agricultural production and employment

Growing seasons, harvests and crops will remain affected well into 2017, with shortages in key agricultural commodities likely to persist even longer. Corresponding contractions in the agricultural sector, and its ability to contribute to employment and GDP growth on a country level will have a number of knock-on effects. This especially in countries where agriculture is a key component of GDP, as is the case in Sub-Saharan African countries.

As can be seen from the chart, the more industrialised regions, such as North America and Europe have limited reliance on agriculture as a component of GDP, or as a source of economic growth. Southern and Eastern Asian nations, after periods of rapid industrialisation and technological leapfrogging, have seen steady declines in the percentage contribution of agriculture to GDP, while the Arab world, Middle East and North Africa are increasingly driven by oil- and oil-related activities. Sub-Saharan Africa, however, still hovers near the 15% mark, levels matched only by small island states in the Pacific and Caribbean. This speaks to some extent to the lack of diversification and industrialisation still prevalent on much of the African continent.

Note: Where data was not available, it has been interpolated.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

Food prices and security

Farming and related activities, including seasonal labour, are the primary source of income in many poor communities. As market adjustments to weather-related headwinds play out, food prices are affected even as jobs and wages are cut, and disposable income shrinks. For the foreseeable future, food prices in Southern and Eastern Africa will remain raised, adding to the upside inflation risks prevalent in the majority of African countries. Since food typically makes up between 40 and 60% of the consumption basket of the poorest in Sub-Saharan Africa (in contrast to below 20% of the highest income segment), rising food prices have the most immediate and acute impact on the most vulnerable communities. The average size of the basket of food shrinks significantly, as does the quality of what fills it.

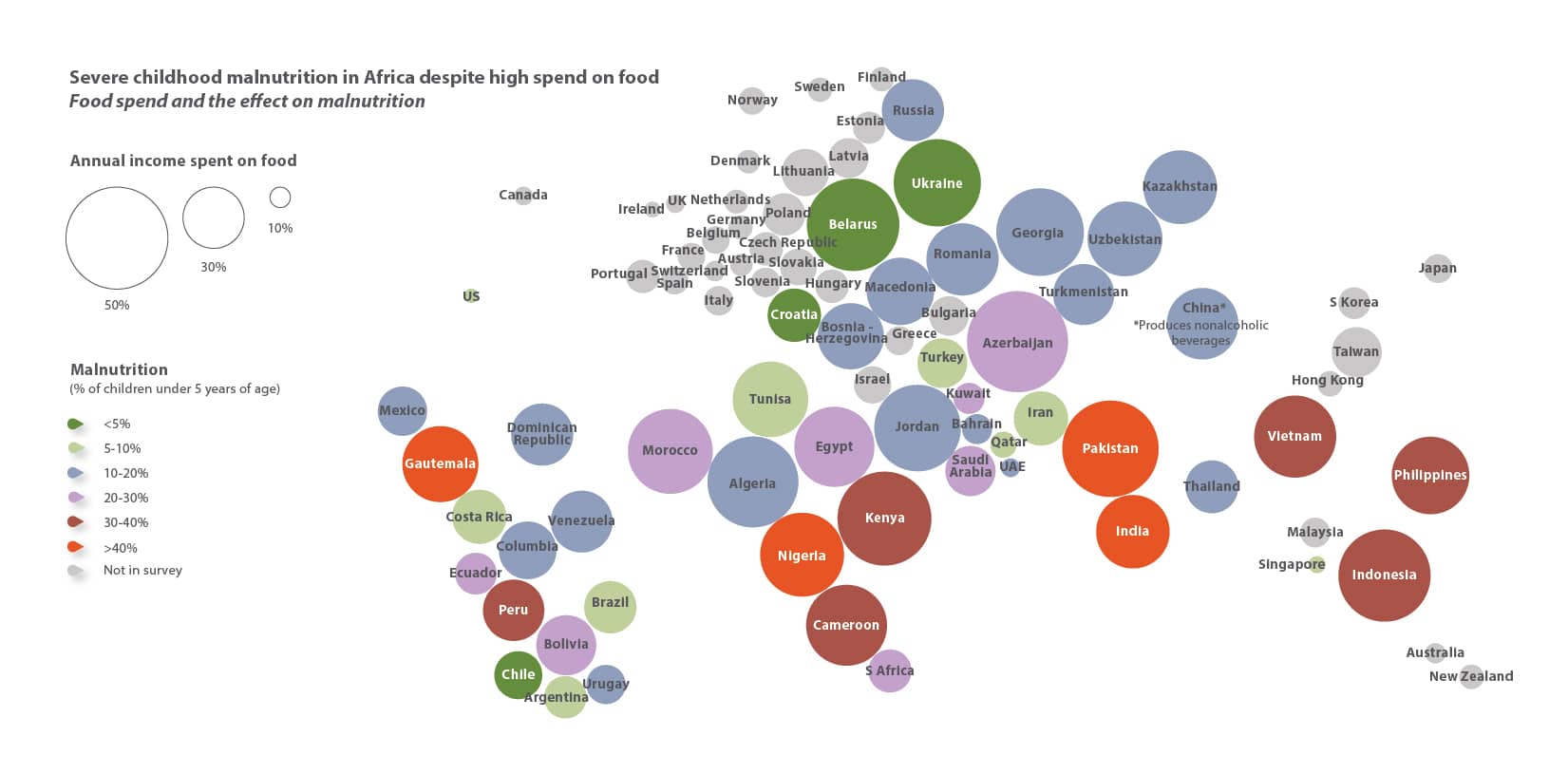

The map below shows that although food makes up a large proportion of household budgets on the continent, it is not sufficient to provide the necessary nutrition to the poor.

Source: Plumer, 2015, Vox

Balance of payments and government spending

When domestic production slows due to adverse weather, food exports (if any) are curtailed, while food imports rise. The size of the impact on a country’s balance of payments depends on the extent to which it previously relied on food imports, versus attaining additional revenue from the export of agricultural commodities. In South Africa, it is estimated that the loss of revenue from maize exports could have a direct impact of nearly R4.7 billion (USD 319 million) on the export side only. The bill from importing between 3 and 5 million metric tonnes of maize will exert further pressure on the balance of trade, especially given the volatile and vulnerable local currency.

In Southern Africa, South Africa and Zambia were previously net grain exporters, mainly to other African countries. As the impacts of El Niño linger, their ability to bridge trade deficits will be severely squeezed with both countries needing to import essential staples, such as maize, themselves. Sourcing staples from further afield, and potentially in dollar terms, adds significantly to the trade bill.

The current global commodity slump, despite some moderation, and the relative strength of the dollar, sees the majority of African governments’ budgets already under pressure. The need to expand social safety nets will only further stress governments’ fiscal positions.

Other Socioeconomic considerations

The ‘weather bandit’ holds individual households hostage: While the immediate needs of a populace affect government spending decisions, behavioural changes occur at household level as well. These changes are at times more subtle than simply reducing the size of the food basket.

Lower nutritional value foods used to bulk up food basket

Alterations to the components of the basket are usually inevitable. When faced with higher prices for some staples, consumers swap them out for others. Quite often, these belly-filling items have less nutritional value: white bread, for example, is typically cheaper (and often subsidised) than maize, and less nutritious and processed meat such as polony (a highly processed meat sausage) may be cheaper than beef, pork or poultry.

Other examples are women in Ethiopia picking seed pods to eat, while children in Malawi are given porridge made from maize husks. This substitution effect is likely to be reversed quickly, as the impact of El Niño recedes, but nonetheless adds to concerns about the nutritional status of the present generation of affected children.

Rising food prices also means that fewer goods can be purchased. The size of the basket shrinks. Some households respond by simply reducing the number of meals each household member has per day. Cultural norms in some countries dictate that women are at the back of the queue when it comes to the size and regularity of meals – having fewer meals can take a very heavy toll on pregnant and nursing women, adding to potential intergenerational impacts (increased incidence of infant mortality, malnourishment and delayed childhood development).

Non-food spending cut back to maintain size of food basket

Households may also be forced to undertake precarious budget-balancing acts. Education and ongoing health needs are often neglected, as are longer-term financial safety measures. With many of the poorest unable to save in the first instance, dissaving is a lesser concern in comparison to increased indebtedness. For example, surveys suggest that already nearly 70% of South African adults do not save at all. The aggregate savings rate in South Africa, already low, will, therefore, decline at least temporarily as a response to deferring savings decisions or dissaving behaviour, since 36% of respondents report that the reason for not saving is that it is simply not affordable.

Households with access to the formal financial sector are often already indebted. These debts require regular repayments, which are not kept up when food expenses soar. For the remainder of the population, limited access to the formal financial sector means that debt is at times incurred through more risky, informal mechanisms including illegal garnishing of wages and the use of loan sharks, adding to household vulnerability. Seasonal workers report that even more risky options – including informal/illegal agreements that put up physical assets as collateral or to allow lenders access to social grants – are often their only recourse. The legacy of this debt will linger long after El Niño is forgotten.

In households with higher disposable income, there is some decision-making room in allocating the budget between different necessary items (beyond subsistence) and discretionary items. In such cases the portion of the pie is allocated to non-subsistence areas (such as household equipment and clothing) shrinks.

In wealthy households, spending on leisure and recreation tends to decline when belts are tightened. At the lower end of the spectrum, however, it is more likely to mean that cash is reallocated from other fairly essential expenditure items. This is likely to mean sacrifices or deferments in household services, health and education spending.

The resulting inter-budget-segment substitution can have longer run impacts on households’ human capital. If one views ‘savings’ as a household budget item, it too suffers.

While allocation decisions are likely to revert to mean, the recovery takes time and the longer run impact on human capital and productivity is difficult to foretell.