China Market Commentary: September 2022

Here are this month’s highlights: The bulk of the manager cohort was underweight to China compared to the neutral benchmark index weight. The median global emerging market manager has also come to realise the importance of Chinese A shares. Among Asian managers, only the 5th percentile had half of their portfolios in the country matching the MSCI Asia ex Japan Index. Managers who historically had a smaller allocation to China were forced to change tack with the opening of the A-share market.

China in September

A relief rally by global equities continued in the first half of August before hawkish comment from the US Federal Reserve meeting at Jackson Hole sent global markets back into a downtrend. Within the Chinese markets, companies listed offshore outperformed their A-share counterparts as news of an audit agreement between the US and Chinese authorities alleviated some concerns over the potential delisting of Chinese ADRs. The MSCI China Index was up 0.2%, while the MSCI China A Onshore index was down 4.6% for the month. Energy and big tech stocks performed well, while some popular sectors, such as electric vehicles and new energy, experienced profit-taking.

Despite strong figures on exports and infrastructure investment, China’s economy remained lacklustre, with manufacturing PMI contracting for July and August. Non-manufacturing PMI expanded, but at a slower pace. Covid-19-related restrictions and a property sector slowdown continued to weigh on economic recovery, while severe drought in the southern region also caused temporary disruption. The Chinese government has released a new round of supportive measures, including issuing more special local government bonds and cutting the five-year benchmark Loan Prime Rate by 15bps to an historic low. With all eyes on the mid-October Party Congress, any indication of a change to the zero-Covid policy will be important and could lead to a consumption recovery.

Manager allocations to China

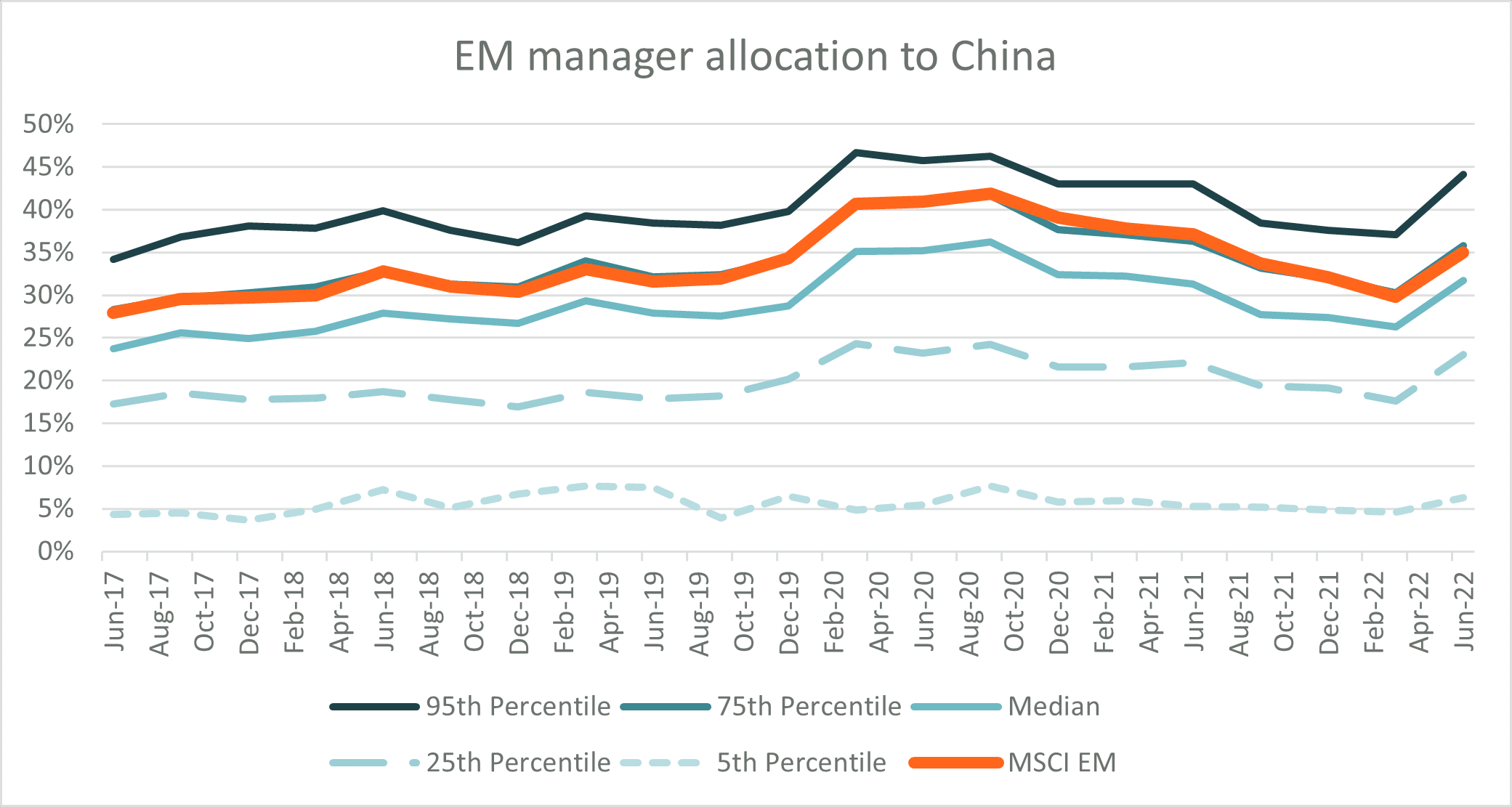

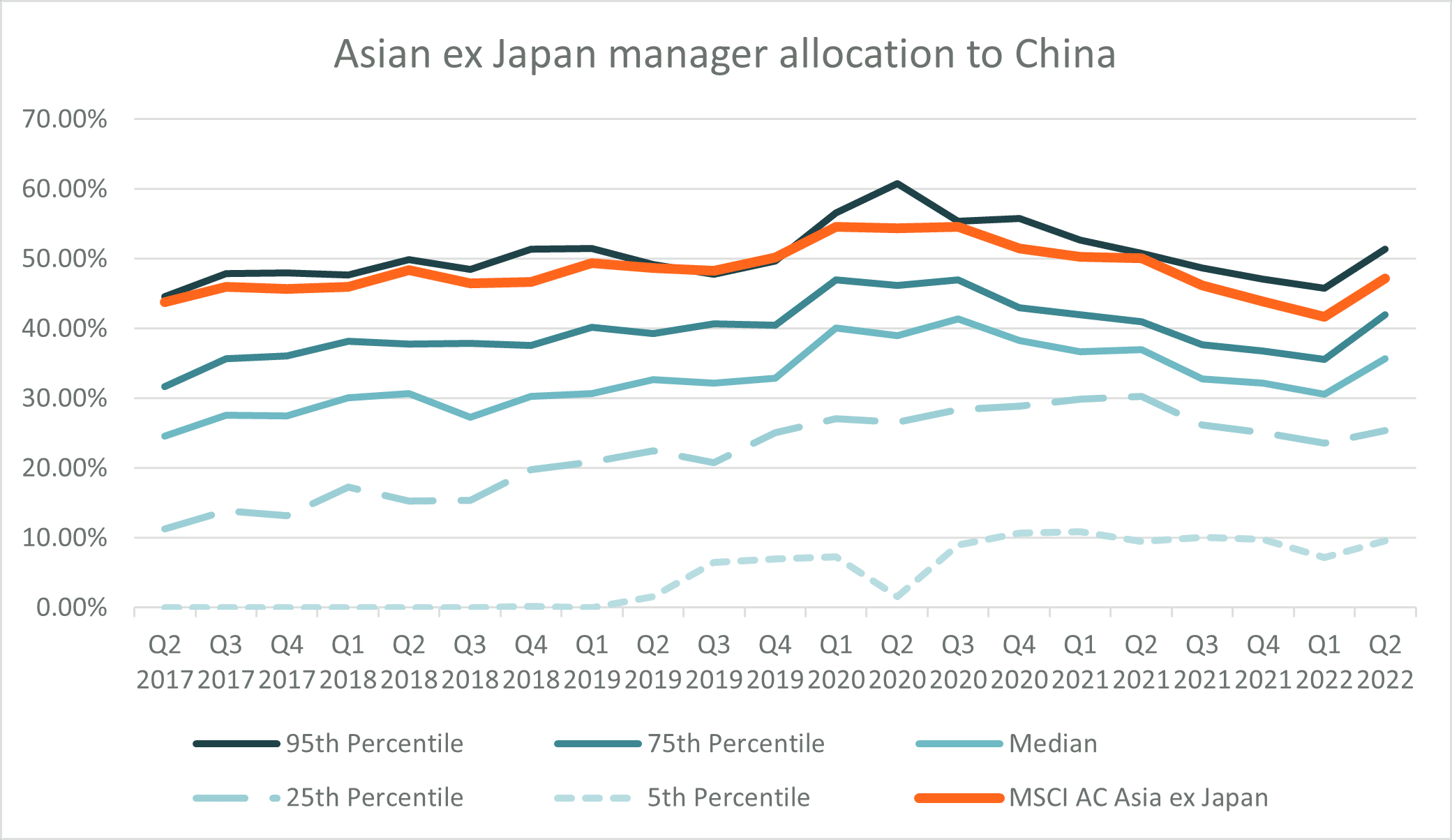

This month, we will examine the allocation to China by institutional asset managers who run global emerging markets or Asian ex Japan portfolios. We were curious to see how active allocations have varied over the last five years. The following graphs show the China allocation for two peer groups consisting of over 500 products in global emerging markets and over 100 products in Asian ex Japan equities.

Source: RisCura, eVestment.

We divided the universe into percentiles according to their allocation to China. The 5th percentile is the managers who were the most underweight, 25th percentile less so, while the 75th and 95th percentiles are those who had the smallest underweight or indeed an overweight position. Examining the chart highlights two features:

- The bulk of the manager cohort was underweight to China compared to the neutral benchmark index weight. Those at the 75th percentile matched the benchmark, and only once you approach the 95th percentile is there evidence of an overweight allocation.

- The extent of the underweight or overweight was fairly constant through time. Managers appear to have maintained an almost “strategic” position to China and have not changed from year to year.

These observations came as a surprise, given the significant turn of events in China, whether it is improved market access, significant growth of the technology stocks before reversing the trend, trade wars, the pandemic, geopolitics and economic volatility. We would have expected a more active approach to managing the allocation to China. Changes by individual managers were either not sufficient to move the averages or were offset by each other.

Source: RisCura, eVestment.

The results are slightly different among the Asian equity managers. They have seemed to reduce their underweighting to China gradually. Their allocations relative to the benchmark were also more sensitive to shorter-term outlooks. The underweighting to China is far larger for Asian managers than for the emerging market managers. China is almost half of the MSCI Asia ex Japan Index and most managers prefer not to have such a high allocation to any single emerging market.

We will now consider the median manager, the bulls and the bears in more detail.

The median manager

The typical emerging market manager maintained about a 4% – 5% underweight to China over the last five years.

A challenge for emerging market managers is that they often don’t have sufficient resources to sift through the thousands of companies in China, and spend extra hours researching these companies, especially in the absence (or certainly lack) of independent research from brokers or banks to ease their workload. A number of global managers have told us that they can go through three to four companies in India or Brazil in the same time it would take them to research a single mid-cap name in China.

With that said, the median global emerging market manager has also come to realise the importance of Chinese A shares. Emerging trends – such as the green economy, electric vehicles, high-end manufacturing and semiconductors – are more likely to be found in the A-share market.

As a result, most emerging market managers based in developed markets are investing to improve their coverage of Chinese companies. This includes recruitment of Mandarin speakers and, in some instances, opening research offices in Shanghai or intending to open offices once travel restrictions are lifted.

Finally, we have seen a greater willingness to invest in the ADRs of large Chinese technology companies whose share prices have collapsed over recent years. Alibaba is held by almost all emerging market value managers that we have come across. Their rationale for investing is that the economic value of these US-listed companies does not change even if they are forced to move their listing to Hong Kong. On the other hand, Chinese specialists, often with a growth bias, are still wary of the larger technology companies. While they recognise that they may be trading below their intrinsic value, they believe that the future growth of these companies will be far more moderate compared to their past.

The bulls

The first point to note is that even managers who are positive about China have not been significantly overweight over the last five years. Among Asian managers, only the 5th percentile had half of their portfolios in the country matching the MSCI Asia ex Japan Index. This may be because there were adequate investment opportunities elsewhere in emerging markets at the time and managers operating in emerging markets typically emphasize country diversification.

Team size doesn’t stop a manager from investing in China meaningfully if they have a positive stance on the country. This cohort has teams of various sizes. We have also found both value and growth managers with an open approach to China and vice versa.

It seems the strategic allocation to the country is almost a separate view, driven by a philosophical assessment of a state-driven country with undoubtedly higher government intervention as opposed to investment style or team size. We found the same to be true for the bears.

The bears

Among the emerging market managers, the lower quartile has maintained an underweight of around 10% – 15% throughout.

This group typically has a very high threshold to include companies listed in China. They would either cite poor governance of companies or the ability of the state to interfere with the running of companies for their reluctance to invest in China. Even if they were reconsidering this view, it was agitated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

We struggle to sympathise with this stance by an emerging market specialist. Governance is a challenge across all emerging markets – not just in China. These same managers often charge premium fees to justify the “more complicated work” that needs to be done to meander the opportunities and challenges in emerging countries.

Asian managers seem to have taken a different approach. Managers who historically had a smaller allocation to China were forced to change tack with the opening of the A-share market, the significant size of the ever-growing Chinese market and that they are “Asian specialists”, after all. The lower quartile’s exposure to China increased from approximately 10% of their portfolio to a peak of 30% last year. Even the 5th percentile increased from no exposure to China to about 10%. While allocation has come off since late last year, it has not been as much as the reduction of China in the MSCI Asia ex Japan Index following the underperformance of Chinese stocks relative to other Asian markets.

Many managers based in Hong Kong and Singapore were historically sceptical of China’s ability to grow its economy sustainably. However, given their proximity to China, they saw the emerging trends and poured significant resources into researching Chinese companies. Many of them launched dedicated China products and set up offices in Beijing or Shanghai if they hadn’t before.

Conclusion

The averages across hundreds of products inevitably hide those hugely successful managers whose allocations have varied over the last five years based on their evaluation of the investment landscape at the time. There are multiple emerging market and Asian managers who have built significant allocations to Chinese companies at times when they were being sold indiscriminately – like during the start of trade wars in 2018 or the regulatory troubles of 2021 – while reducing their exposure at other times.

We did this research expecting large variations in global emerging market managers’ allocations to China. We were surprised to find that institutional managers in this asset class have, on aggregate, been more strategic in nature and maintained their position, both positive and negative, regardless of the multiple events that have happened in the country over the last five years.