The effect of El Niño on key Southern African countries

The following section has a strong South Africa focus (the country considered best prepared, and where data is most readily available), which is used to illustrate some of the ripple-effects. Similar analyses can be applied on a regional or country basis.

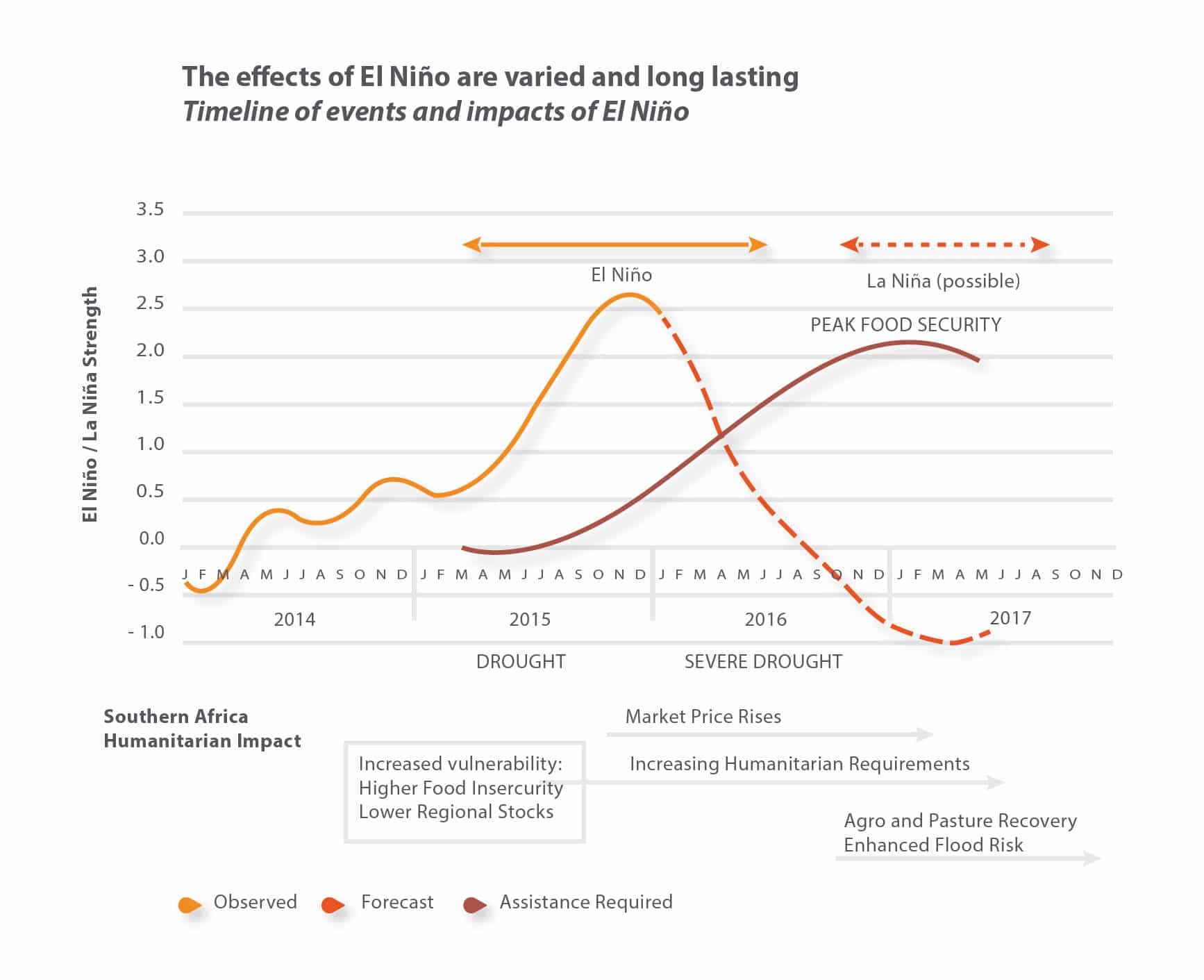

The chart below shows the World Food Programme’s projected timeline for how El Niño will continue to impact food insecurity, food prices and humanitarian needs well into 2017.

On 16 March 2016, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) declared a regional drought disaster with Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Swaziland in the grip of the adversity.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe, having earlier declared a state of emergency, had for an extended period been appealing to global agencies and receiving food aid. Agriculture on a commercial scale in Zimbabwe is severely limited, and the impact of declining production on government revenue and overall job creation is therefore muted. The fragmented nature of agriculture and the prevalence of subsistence farming have left the country reliant on imports from neighbours – imports that have largely dried up. Rising food prices are fuelling already rampant inflation, and further exacerbating food insecurity. An uneasy political situation, the reluctance or inability of leaders to implement reforms, and an already challenging economic environment has meant that the government is struggling to plug any gaps.

Lesotho

In Lesotho, more than 25% of the population is estimated to remain food insecure until June 2016, with further deterioration of the situation expected into the beginning of 2017. This small nation is dependent on food imports from neighbouring South Africa, with limited local production. The current depressed commodity outlook and close ties to the South African mining industry as a source of remittances, has already seen household budgets under strain. Reduced availability of imports, rising food prices, reduced remittances, and inadequate safety nets have seen poor households experience a nearly 44% decline in their food and cash income compared to normal levels.

Swaziland

Swaziland is facing widespread water scarcity, and local production of the staple food, maize, is expected to decline by nearly 64% over the extended period. Some 300 000 people, again nearly a quarter of the population, require food assistance. Added to the challenges the Swazi government faces, water scarcity is affecting sanitation and health facilities. Water authorities in Namibia and Botswana, as in Swaziland and elsewhere, have imposed water restrictions. As well as the direct impact of rising grain prices, both Namibia and Botswana have felt the effects of El Niño related feed shortages in livestock production.

Malawi

Malawi has been hit by a double-whammy, with the combined effect of drought and flooding resulting in the most severe food crisis in a decade. The country declared a State of National Disaster on the 12th of April 2016, with the President citing a projected deficit of over 1 million metric tonnes in the staple food (maize). Maize prices have already increased by more than 75% from last year, as production continues to suffer.

Zambia

Zambia, previously a net exporter, has banned grain exports. The country is using fast-dwindling currency reserves to import maize, further squeezing already strained government resources. Due to the low water levels in the Kariba dam (between Zimbabwe and Zambia), authorities in both these countries have been forced to limit hydro-electric generation, causing wide spread power outages, and exacerbating the effects of the slowdown in both economies.

South Africa

Apart from South Africa, the region has proven ill-prepared for both the immediate and ripple impacts of El Niño-related weather disruptions. While South Africa had better response plans in place, the country hasn’t escaped the effects of El Niño.

Impact on inflation

The largest producer of maize on the continent, South Africa has been forced to import both the yellow and white varieties (1.73 million and 72 000 tonnes respectively as at end April 2016). A shortfall of 3.8 million tonnes is anticipated for this year. Maize prices have been peaking with the staple fetching nearly 20% more per tonne than a year ago, at R4000 – R5000 per tonne (USD 270 – USD 340). The knock on impact on overall food inflation, and headline inflation has been somewhat delayed for at least two reasons: In the first place, processed items (such as samp and maize meal) typically have a lag of 6 to 9 months before reflecting input-price hikes, and the lag for dairy, eggs and meat are slightly longer.

In the second place, retailers have been absorbing the brunt of the extra costs over the course of the past year, effectively subsidising cash-strapped consumers. It is clear, however, that retailers, particularly in the current domestic economic environment, can only withstand so much margin-squeeze. Rising costs at producer level are increasingly likely to be passed through to the consumer.

Changing food prices

The chart below shows the progression of food price inflation on a monthly basis since 2012. Food prices are notably volatile; nevertheless, prices have escalated sharply since December 2015. This coincides with the estimated timeline for the worst of the ongoing and after-effects of the El Niño-related drought.

Source: StatsSA

Looking at the chart below, the relatively benign increase in meat prices is largely attributable to the forced thinning out of herds, as feed became in ever-shorter supply. As at January 2016, farmers had been forced to cull 225 340 livestock. Economists expect that food price inflation will peak at about 13% later this year.

Source: StatsSA

Agricultural production and employment

Declines in agricultural production saw the gross value of the agricultural sector contract by 12.5% in the third quarter of 2015, with further declines anticipated as the episode subsides. While agriculture contributes a relatively small share to overall GDP in South Africa (roughly 2.5%), it is one of the key sectors providing employment, particularly to rural households. Official measures of unemployment indicate that sector employed

about 700 000 people in South Africa as at September 2015. This labour-intensive industry, therefore, accounted for roughly 4.6% of total employment. Statistics SA suggests that the agricultural sector shed 37 000 jobs in the last quarter of 2015, due to the ongoing drought, with losses set to continue as the reduced summer crops are

harvested. The country, already burdened by a record-high unemployment rate of 26.4% (March 2016), can ill afford further cutbacks.

Farmers in rural areas are particularly concerned about the potentially underestimated impact on seasonal employment, and the effects on businesses in agricultural communities. Seasonal work is the main source of income in many rural communities, while a number of small businesses, particularly in the service industry, are built on the custom of farmworkers. Even larger traders, who sell chemicals, fertiliser and seeds, are faced with declining demand or are feeling their balance sheets strained by delayed payments by cash-strapped farmers.

Farmers face increasing levels of debt, often having borrowed against the expectation of future yields. The Land Bank estimates that Total Farm Debt increased by nearly 20% between December 2014 and June 2015, with further delays in payment likely to exacerbate the current trend. Anecdotally, farmers confirm having nearly decimated

their savings in efforts to alleviate the current dry spell. They also indicate that lack of access to insurance and further formal sector funding mechanisms present a serious problem.

Rising cost of the drought – debt and government spending

Insurance companies that would traditionally have provided multi-peril crop insurance (MPCI) have been unwilling to accept new applications for the 2015/2016 planting season. From their perspective, new applicants present a poor risk profile, given the poor previous season and gloomy prospects, and are only electing to participate in drought-affected times, making the business model for long-run insurance provision unsustainable.

The government will also be required to budget for the cost of providing interim assistance and for the cost of getting farms back on track. The ministry for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has thus far allocated R1 billion (USD 68 million) to agricultural drought relief and indicates that it is still awaiting further injections from national coffers, but that R24.6 million (USD 1.67 million) had already been spent on assisting farmers in drought-stricken areas (at end April 2016). Within the context of the timeline – with El Niño impacts still to play out well into 2017 – direct assistance, the mitigation of the effects of rising food prices, alleviating job insecurity, and addressing future funding needs will continue to drag on government finances.