Investing into private equity for African institutions

Institutional investment is a key driver of the development of capital markets. But, in many parts of Africa, institutional investment has been slow to develop and development finance institutions (DFIs) have long filled this gap. In recent years, pension reform in many countries has driven the creation of more reliable forms of savings for individuals. While the assets in African pension funds are still relatively small, most are fast-growing, creating local pools of capital for investment.

The traditional pension system works on the premise that members are formally employed, work for 40 years and contribute regularly during this period, resulting in suitable retirement savings. However, an issue that continues to impact the growth of pension fund assets is that in many countries much of the population is employed in the informal sector.

Looking at sub-Saharan Africa, for example, retirement remains the preserve (and luxury) of the few employed by the formal sector. For most, working well past the ‘traditional’ retirement age of sixty-five is a norm. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs reports, among those Africans above the age of sixty-five, 52% of males and 33% of females were active in the labour force in 2015. The reality is that the majority of older persons in sub-Saharan Africa have no choice but to continue to work for as long as they are physically able, due to the absence of adequate savings.

The small size of the current pools of capital notwithstanding, there is money to be invested. The question is, where?

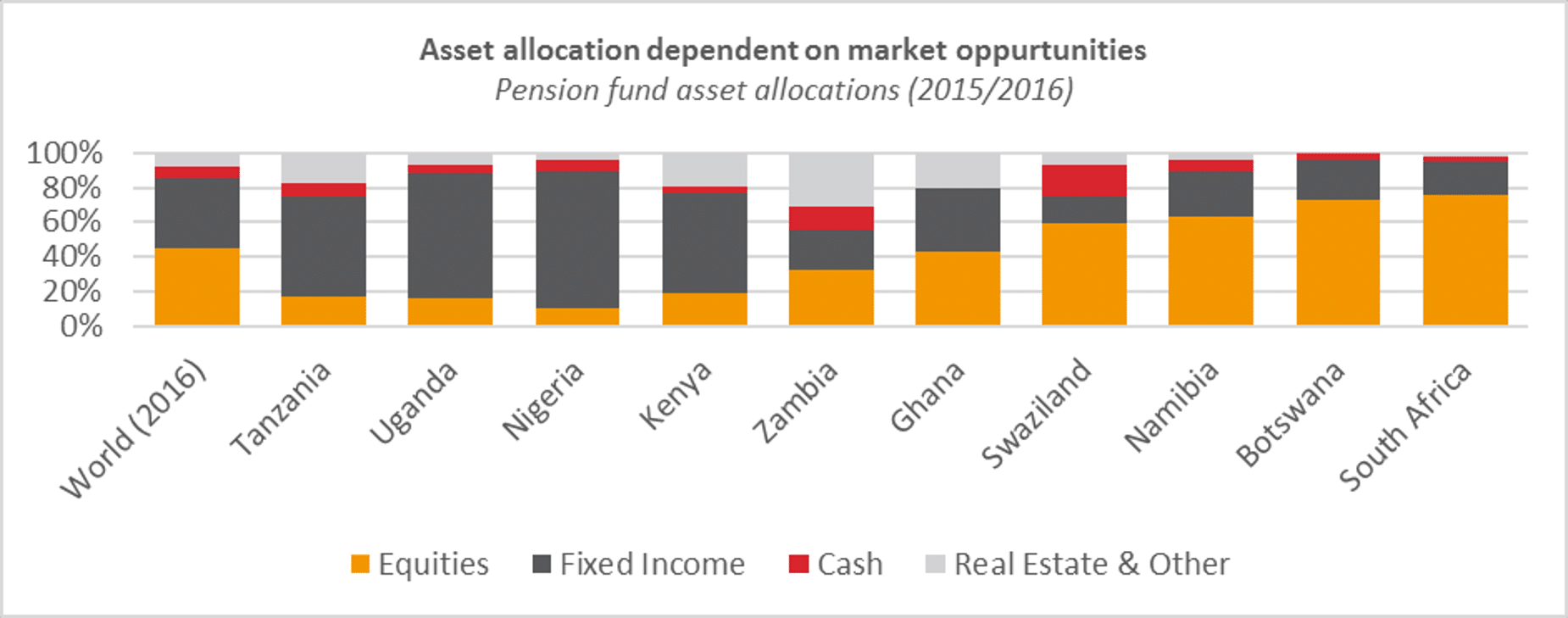

In most OECD and many non-OECD countries, bonds and equities remain the two predominant asset classes for pension funds. While globally there is a larger allocation to equities (45%), the picture in Africa is more disparate. Asset allocation in sub-Saharan Africa in particular has favoured equities, which have shown a steady increase enabled by the development of capital markets and regulatory change.

However, liquidity and the cost of trading remain problematic when investing in African listed equities. Outside of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, Africa’s bourses remain stubbornly illiquid, with Egypt’s stock exchange, Cairo and Alexandria Stock Exchange (CASE), currently exhibiting the second highest daily turnover across the African exchanges with a total of USD 72m traded daily, compared to the JSE’s USD 1 800m.

The next most liquid exchange, by turnover for 2018, is the Moroccan stock exchange (CBSE) followed by the Nigerian stock market (NGSE), at USD 17m and USD 15m respectively, but this still represents less than 1% of the trade on the JSE.

In terms of trading costs, it is difficult to obtain reliable information in Africa. Overall, the cost of trading on African exchanges is considerably higher than developed markets, and a substantial portion of trading fees is made up of brokerage commissions.

When considering the low levels of liquidity and high trading costs in Nigeria and East Africa, it is not surprising that asset allocation is dominated by fixed income allocations in these regions, which predominantly constitute local bonds. When viewed alongside the high asset-growth in these regions, it reflects both regulation and a lack of alternative local investment opportunities. This highlights a key challenge pension funds face; identifying enough appropriate, local investment opportunities to invest ever-increasing contributions.

Local regulation remains one of the main drivers of asset allocation. There are often significant differences between the regulatory allowances for pension funds, size of local capital markets and actual portfolio allocations between regions. This is reflective of a number of factors including familiarity with alternative asset classes, such as private equity, development of local capital markets and availability of investment opportunities. In many countries, assets are growing much faster than products are being brought to market, limiting investment opportunities if regulation does not allow for pension funds to invest outside of their own countries.

Private Equity

One of the ways that the current shortage of investment opportunities can be addressed, is through investment into alternative assets classes like private equity.

Globally, alternative assets have been increasingly prominent in institutional investors’ portfolios, partly driven by the continued low interest rate policy around the world. The vast majority of institutions now commit to at least one alternative asset class, and the level of participation is particularly high across more established asset classes such as private equity, real estate and hedge funds. We are entering a period where alternatives are no longer ‘alternative’ in the eyes of many institutions, which bodes well for further industry expansion.

While investment in alternative assets in emerging markets has historically come from DFIs, pension funds are slowly joining in. Local institutional investors lend credibility and often serve as a catalyst for greater external interest. Local investors also allow global peers to leverage local knowledge and networks.

Regulation

A number of countries including South Africa, Botswana, Nigeria and Namibia have led the way in investing in alternative asset classes such as private equity. South African pension funds, for example, have been active in African private equity investment, both locally and across the continent, enabled by regulatory change.

According to the SAVCA 2017 Private Equity Industry Survey (covering the 2016 calendar year), funds under management for the South African private equity industry grew from R158.8 billion in 2015 to R171.8 billion in 2016.

Pension and Endowment Funds were the main source, 40.2%, of all third-party funds raised during 2016, (2015: 35.3%). Governments, aid agencies and DFIs accounted for 20.6% in 2016 (2015: 19.6%) and insurance companies/institutions made up 19.6% of funds raised in 2016 (2015: 8.4%).

An example of a country where regulatory change has not enabled investment into private equity is Nigeria, where in 2010 the regulator for pension funds, National Pension Commission (PENCOM), made investment into private equity allowable up to a 5% limit, raising hopes for local investment into the industry. Using 2016 figures, represents potential Limited Partner (LP) commitments of an estimated USD 842m. However, PENCOM also prescribes additional restrictions such as a minimum of 75% of the private equity fund to be invested in Nigeria, registration of the fund with the Nigerian SEC, and a minimum investment of 3% in the fund by the General Partners (GP). These regulatory restrictions make it difficult for LPs to find sufficient suitable investments.

Although the less regulated and direct nature of private equity does represent higher risk than traditional asset classes such as bonds and listed equity, being over prescriptive by means of regulations is not a replacement for good risk management processes within an institution.

Deregulation of prescription and sound investment practices by institutional investors will unlock capital flow to suitable investments opportunities wherever they may present themselves in Africa. If African pension funds are to take the lead from DFIs in further deepening the private equity industry, capital must be allowed to seek the most compelling investment opportunities.

Comfort with the asset class

Investment into alternative assets requires specialist knowledge and risk management. For pension funds to invest in these assets classes and still ensure the highest level of care is taken with members’ assets, they will need the support of experts. In many markets, the use of asset consultants in this role is still in its infancy and advice is often obtained from actuaries or even asset managers. The private equity industry bodies, trustee associations and regulators will need to focus on providing on-going training to slowly build an understanding of and comfort with the asset class.

Availability of appropriate products

Due to the relatively small size of pensions funds in Africa, it may be difficult to obtain sufficient diversification. Similarly, it may be difficult for the fund to commit sufficient resources to manager research and selection. Normally these would be circumstances in which a fund of fund option could be considered. However, the requirement in many markets for pensions funds to invest geographically within country, makes this difficult. The majority of private equity funds are either pan-African, or at least invest over several key markets.

It is clear that there are a number of enabling factors that are required to ramp up institutional investment into private equity that need to be addressed to create a viable eco-system. Currently capital is being created, regulation is being refined, industry education has started and increasingly players in the asset management industry are looking at how to structure products to enable the participation of local pension funds. One day soon all these factors will come together and leverage investment into this industry to new heights

Heleen Goussard,

head of Unlisted Investment Services, RisCura

* This article was originally published online by Capital Markets in Africa.