China Market Commentary: February 2023

Here are this month’s highlights: In just two years, the MSCI India Index’s weighting to Adani companies increased from 1.2% to 5.8% in aggregate, despite many people’s concerns of poor governance. A key question that arises as a consequence of this saga is whether the “E” (within ESG) was so compelling that the “G” could be compromised. By Western standards, one of the main reasons for the poor governance in emerging markets is due to the presence of a controlling shareholder – usually the founder and their family, or the state. Private enterprises run the risk of being managed for the benefit of the majority shareholder and not stakeholders in general, which in its extreme could lead to fraud. In the private sector, we all know how much value a visionary leader, usually the founder and controlling shareholder of the business, can create over time by focusing on the strategic plans rather than quarter-over-quarter financial results – think of the founders of the great internet companies. While it is not always black or white, we argue that fund managers should always be careful when taking on poor governance as the results could be binary – all or nothing.

Adani & Governance in Emerging Markets

In January, Chinese equities experienced a broad-based rally, with the MSCI China and MSCI China A Onshore indices rising by 11.8% and 10.4%, respectively. The reopening of the economy after the lifting of Covid restrictions and expectations of a swift recovery buoyed investor sentiment. Portfolio flow data indicates that foreign investors continued to add China exposure. After removing the zero-Covid policy in early December, China has quickly passed the peak of its infection curve and appears to have reached herd immunity within a month. On the ground, life is almost back to normal.

On the macro side, both manufacturing and non-manufacturing PMI rose into expansionary territory in January after the December trough. In their 2023 work reports, local governments across the nation reiterated the importance of reviving economic growth this year. We expect to see the GDP target and policy directions in the upcoming National People’s Congress when the new government comes into office.

Turning to India, about a month ago significant concerns regarding the governance of the Adani Group of companies were raised by Hindenburg Research, a US short seller. Accusations of stock manipulation and accounting fraud erased more than 60% from the value of Adani’s publicly traded companies and rocked an empire that spans from ports to energy. While the drama is still playing out, it is yet another case study demonstrating the importance of governance in all markets, especially within emerging markets (EM), which is the subject of this month’s letter.

The rise and fall of Adani companies

The Adani group of companies spans across power generation, green energy, ports, airports, other infrastructure and multiple other industries.

Adani Green Energy was perhaps the most famous in this family of companies, given its ambitious plans to contribute towards the transformation of India’s energy production to solar and wind. Last year, its market capitalisation increased from USD28bn to USD59bn by mid-year, before coming back down to USD37bn at the end of the year. It now stands at USD9.5bn. It was a popular stock among ESG-focused funds.

In just two years, the MSCI India Index’s weighting to Adani companies increased from 1.2% to 5.8% in aggregate, despite many people’s concerns of poor governance. Interestingly, we have not met any Indian equity manager that held any of the Adani companies, and omitting such would have been one of the largest detractors to relative returns over this period. Furthermore, most of the concerns raised in the Hindenburg report were already well known, and the subject of multiple media reports.

A key question that arises as a consequence of this saga is whether the “E” (within ESG) was so compelling that the “G” could be compromised? Were some of these ESG funds simply tracking ESG indices or had they simply not done their research correctly? Or were they, or the ESG index providers, just too distant from the reality on the ground? And what is the reality? The saga has not been concluded yet.

We believe that in emerging markets, governance is the single most important factor that needs to be focused on. Analysis should be tailored to each country’s cultures, customs and norms. Ultimately, a well-run, sustainable company should have a better approach to the Environment and Social aspects that affect all stakeholders. However, Adani Green Energy shows that the reverse is not necessarily true and can lead to big losses (meaning a company with good E but poor G). It is also a stark reminder that passive investing in emerging markets can be risky, even if it may take many years for a manager to be vindicated for avoiding a company with poor governance.

China is behind in best practice corporate governance

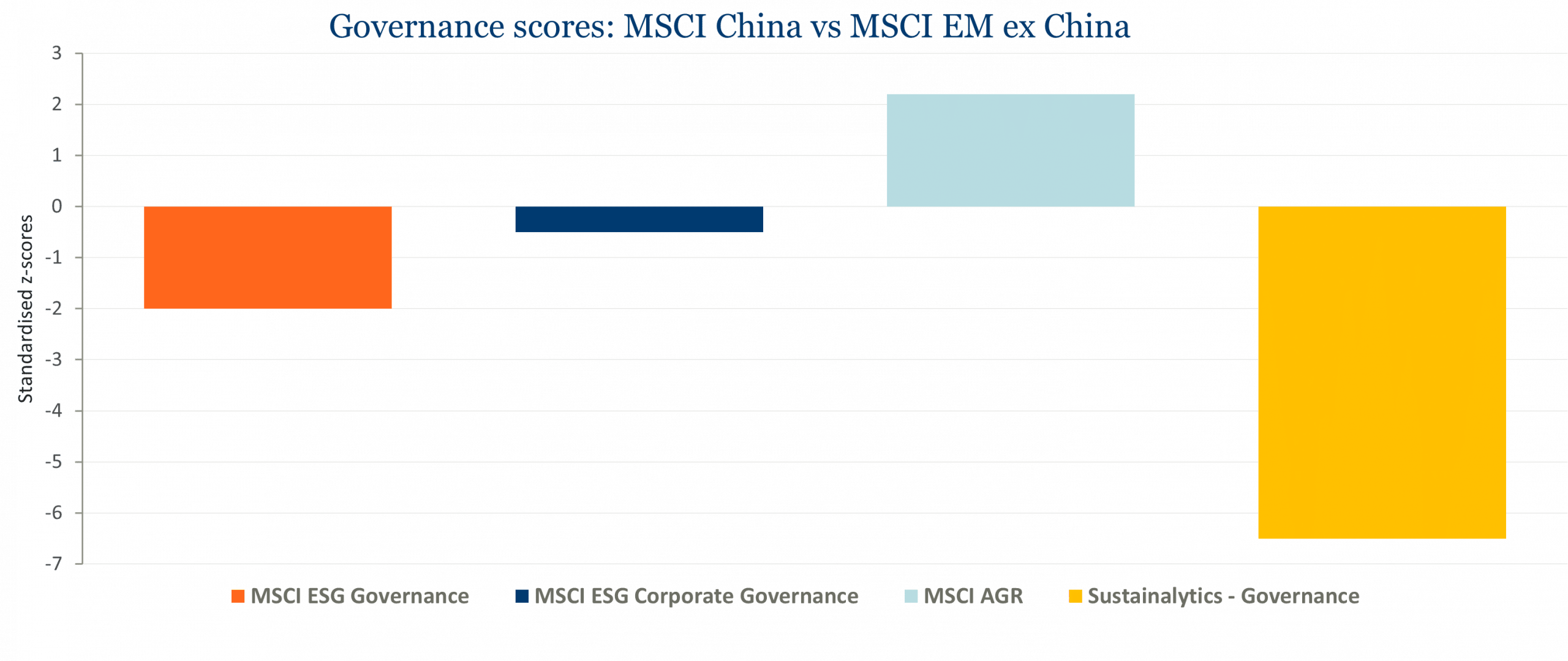

Corporate governance standards in China lag behind those of developed markets. The following chart shows the standardised deviation of MSCI China from MSCI EM ex China based on various rating agencies (a deviation of more than 1 should be taken as a significant difference):

Source: Style Analytics

One needs to be cognisant of who is compiling the data and how it is interpreted. For example, there is a significant difference between how MSCI and Sustainalytics (both ESG data collectors) see China relative to other emerging markets. Sustainalytics numbers show that governance in China is well behind the other emerging markets. MSCI, on the other hand, argues that while overall governance in China (corporate governance, business ethics, government and public policy) lags behind that of emerging markets, corporate governance on its own is similar. Accounting standards (as measured by MSCI AGR) are better in China than in other emerging markets.

By Western standards, one of the main reasons for the poor governance in emerging markets is due to the presence of a controlling shareholder – usually the founder and their family, or the state. These companies will almost always fall short in corporate governance best practice. No successful entrepreneur wants to relinquish control. This is true everywhere: witness Facebook controlled by Mark Zuckerberg or Tesla by Elon Musk, who both resist attempts to have independent oversight. The same applies to state-controlled companies.

Where there is a controlling shareholder, it is far more important to understand the alignment of interests with minority shareholders than, for example, the composition of the board or how it operates. A good board means little if the controlling shareholder or management has bad intentions. In emerging markets it’s essential to do the homework on the controlling shareholders, assess their historical actions and understand their quality and integrity.

Not all these companies are poorly governed. They should, and often do, follow other best practices in corporate governance, such as establishing compensation and audit committees and having non-executive directors. Overall, emerging markets are seeing a steady improvement across the board in corporate governance.

There are idiosyncrasies that we need to study on a case-by-case basis. Each country has its own specific peculiarities. China is dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which means potential state interference in business affairs, whereas corporate India is run by large family dynasties. Korea has chaebols and complex cross-shareholding mechanisms. Our Stewardship surveys of the Chinese (2022) and South African asset management industries (2021) go into further detail and are available on our website1. We look forward to publishing our findings on India later this year.

Dangers of partnering with bad operators

Chinese SOEs are at risk of being run for the benefit of the state, or used as a policy tool, and consequently may not be focused on an ordinary corporate mission. The Chinese state-owned commercial banks are good examples. During the pandemic they were asked to increase lending and provide relief to small businesses despite rising defaults and falling profitability. Even if that is not the case, most SOEs often tend to fall short when it comes to best business practices and are run far more inefficiently when compared to private enterprises.

On the other hand, private enterprises run the risk of being managed for the benefit of the majority shareholder and not stakeholders in general, which in its extreme could lead to fraud. There have been many well-publicised cases demonstrating just that, such as the reckless debt-ridden developer Evergrande, the accounting frauds of both Luckin Coffee and Leshi, and share price manipulation of Kangmei Pharmaceutical.

Outside of China, Steinhoff, one of the largest listed stocks on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, lost most of its market capitalisation in 2017 on the back of alleged accounting fraud. On paper, Steinhoff had scored well on corporate governance. Another example, Lojas Americanas, a Brazilian retail chain, is currently going through its own scandal. Investors of these companies and many more incurred heavy losses when their share prices eventually collapsed.

The upshot is that it is very important to do the work to understand who you are effectively partnering with. If there is a genuine alignment of interest these businesses can deliver strong long-term returns for shareholders.

Examples of good partners

China Resources Land is an example of a well-governed and market-driven Chinese SOE. Typically, one would not expect an SOE to have good governance due to the controlling influence of the state. China Resources Land develops residential and commercial properties and operates the largest luxury shopping mall portfolio in the country. It has a strong management team which is incentivised to achieve long-term growth targets. As such, not only does it enjoy access to cheap financing and good land resources as an SOE, but it is also managed like a private enterprise. Despite a challenging environment in the property sector, the company continued to deliver double-digit earnings growth in the past year and generate strong absolute and relative share price returns. Other examples include China Mobile and China Tourism Group Duty Free.

In the private sector, we all know how much value a visionary leader, usually the founder and controlling shareholder of the business, can create over time by focusing on the strategic plans rather than quarter-over-quarter financial results – think of the founders of the great internet companies. LONGi Green Energy Technology is another example. It is an integrated solar technology company and the world’s largest mono silicon wafer producer, and scores highly on governance measures relative to its domestic peers despite having its founder as a majority shareholder. The company does particularly well on board/management quality and integrity, remuneration disclosure, and ESG governance and reporting standards.

It’s not always black or white

Forming a view on the governance of these companies is not always easy. JD.com, the second-largest e-commerce platform in China, is one such example. About 75% of voting power is held by its founder, Richard Liu, through a dual class share structure commonly used by technology companies. Under Richard’s leadership, JD built its own nationwide logistics network even though many investors did not like this (capital-intensive) idea. The company was not profitable for a long time and saw its share performance significantly below that of competitor Alibaba from 2017 to 2018. Some reputable fund managers stopped just short of calling it fraud.

But Richard’s strategy was eventually proven right. JD turned profitable in 2019 thanks to margin improvement from economies of scale and its differentiated better-quality delivery services. Since September 2014 (when Alibaba was listed) to date, JD’s share price has outperformed Alibaba’s by over 60%.

What about SOEs selling excellent products and delivering incredible profits for decades? Moutai is arguably the highest-quality beverage company in the world. It owns the best brand in the largest country in the world. It can be difficult to resist the temptation to invest in a company like that.

On the flipside, what about companies where the share price more than compensates for poor governance? These companies are often targets for value managers.

While it is not always black or white, we argue that fund managers should always be careful when taking on poor governance as the results could be binary – all or nothing.

Risk of underperformance while the music is still playing

It can be very difficult to tolerate poor relative returns when a company with poor governance enjoys strong share price performance “while the music is still playing”. Avoiding the stock becomes even more difficult when these companies become larger components of benchmark indices, as was the experience of Indian fund managers in the case of Adani companies.

Most emerging market countries/regions have concentrated stock markets where this can happen. In the case of Steinhoff, originally a furniture manufacturer, peer pressure (from relative performance, say) drove fund managers to finally cave in despite years of calling out bad governance while its share price kept climbing. In a few instances, some shareholders bought shares for the first time just before the company finally collapsed in 2017.

Emerging markets fund managers must have the discipline to deviate from their benchmark to avoid poorly governed companies even if it leads to poor relative returns in the short term. Properly analysing companies for governance risks is time-consuming and requires specialist managers. It is one of the main reasons why we like country managers. While well-governed companies in emerging markets may not meet the developed market standards of corporate governance, they can deliver excellent returns for those managers that are willing to understand them properly.